“Where’s the MTA Capital Plan?” Public Kept in Dark on 2020-2024 Plan

Where’s the 2020-2024 MTA Capital Plan?

One of Most Secretive Processes Since Capital Plans Began in 1982

Review of Past Plans Shows 2019 Process is Unlike Any Other Year, Diverges from Transparency Norms

August 2019

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Board is slated to vote on the 2020-2024 capital plan on September 25th. Capital plans are approved every five years and are massive documents filled with crucial details that assign tens of billions in spending and are the basic list for MTA priorities. Previous draft capital plans have been made public as early as March. Yet, with only five weeks until the board vote, this capital plan has been kept secret from the MTA Board, legislators and the public. (Notably, an MTA consultant, AlixPartners, revealed they reviewed a draft weeks ago.1)

Adding to the secretiveness, the MTA has also not released a 20-year needs assessment, a report intended to show the MTA Board, Legislature and public how much funding should go to restoring aged and deteriorated infrastructure. The 20-year needs assessment is supposed to inform the capital plan and be released and discussed before the plan is formulated and voted on. Since earlier this year, elected officials and advocates have repeatedly asked the MTA to publish the needs assessment.

Reinvent Albany researched past capital plans and found that in nearly every other capital plan cycle, the public had more information about the MTA capital plan before decisions were made. By historic standards it’s late in the game, but there is still time for the MTA to create some basic transparency around the 2020-2024 capital plan. Reinvent Albany recommends the following documents be released now, with all schedules and projects lists provided in an open data, spreadsheet format:

- An updated 20-year needs assessment, covering 2020-2039

- The draft 2020-2024 capital plan, as anticipated to be voted on by the MTA Board on September 25, 2019

- The MTA’s submission to the Federal Transportation Administration (FTA) for its Transit Asset Management Plan (TAM), including narrative strategic plans and any associated data lists

The MTA’s current capital plan process was born out of a funding and service crisis. Beginning in 1979, then-Chairman Richard Ravitch worked with the State Legislature and Governor to both secure funds and develop a process that has largely worked well to deliver capital dollars to the MTA and provide public accountability for spending. The capital plan process is structured around an inventory of assets, a needs assessment (first released in 1981 for a 10-year period), a draft and then a final five-year capital plan, the first of which ran from 1982 to 1987.

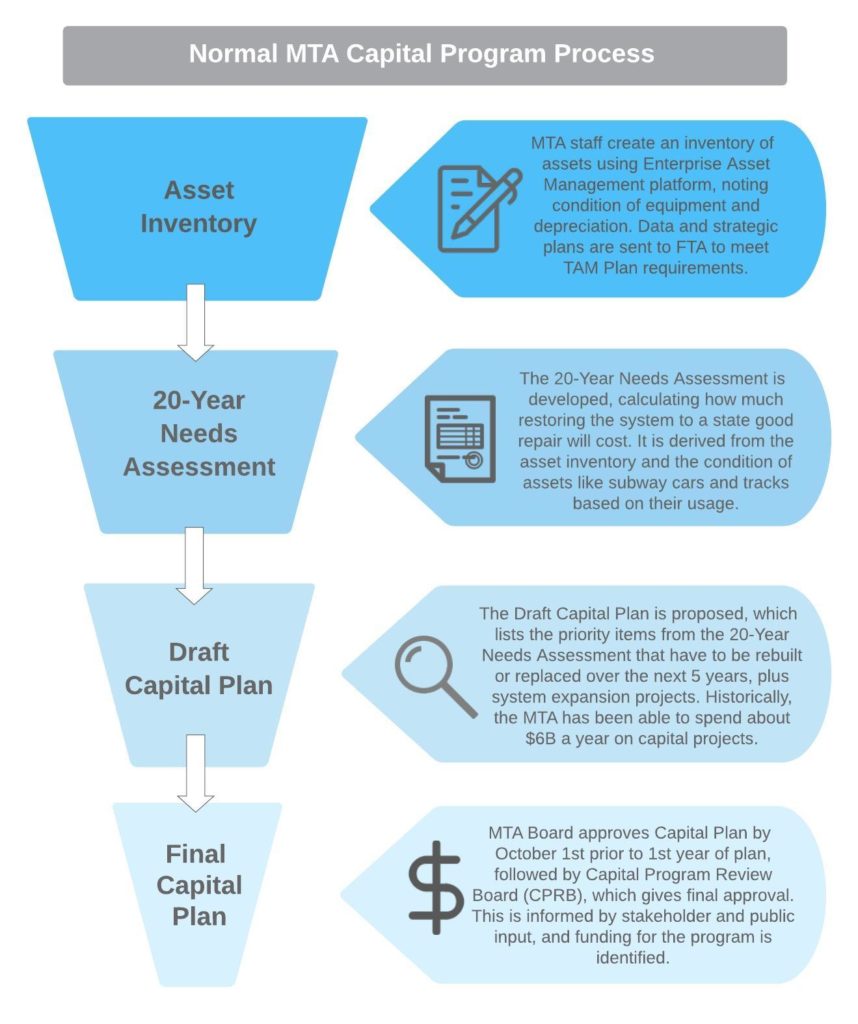

Based on the model developed in the early 1980s, a normal MTA capital plan cycle has four steps:

- The MTA develops an inventory of assets, noting the condition and deterioration of their asset base, including everything from train cars to buses to tracks and stations. (Now incorporated in the Transit Asset Management Plan or “TAM” which is submitted to the Federal Transit Administration.)

- The asset inventory informs a 20-year needs assessment, which includes a calculation of the cost of restoring the system to a state of good repair and any other improvements.

- The needs assessment informs the development of a draft capital plan, which lists specific projects that have been scoped out.

- A final capital plan is approved by the MTA Board and sent to the Capital Plan Review Board (CPRB) for approval, which ensures that there are funding sources identified for projects.

A chart of the capital plan process follows.

The MTA has described the importance of the 20-year needs assessment in prior documents, showing its value for their own planning process (emphasis added):

2015-2019 Capital Program: “To develop the 2015-2019 Capital Program, we analyzed the building blocks of our system and the trends that will shape the next 20 years of regional mobility—a process we call the Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment.* Through this structured, two-year process, we developed a picture of the next twenty years of capital investment by merging investments that renew our assets—promoting what we call a ‘state of good repair’—with ‘vision’ investments that enhance and expand the system in step with changing regional demands.”

Final Environmental Impact Statement for East Side Access: “Prior to the preparation of each 5-year Capital Program…MTA prepares a 20-year assessment which reviews the long-term capital infrastructure needs of each of its divisions. These assessment reviews include an update of the condition of capital assets; a projection of the level of investment required to reach or maintain the systems in a state of good repair and to meet future demand; and a statement of investment priorities and strategies. The 20-year needs assessment serves as the foundation for developing the 5-year plans. It assesses the condition of agency capital assets and develops investment strategies that reflect the agency’s long-term service plans. The 5-year capital program is a product of a 20-year needs assessment that must be prepared by all of MTA’s operating agencies.”

The MTA and Legislature know the 20-year needs assessment is important and fundamental to a rational, needs-based capital plan. The state budget passed in April 2019 (FY 2020) requires the MTA to release its 20-year needs assessment for the 2025-2029 plan by October 1, 2023, though it neglected to address the current cycle.

The public would also benefit from disclosure of the Transit Asset Management (TAM) Plan that was due to the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) in October of 2018, as this data overlaps with the MTA’s own asset inventory (developed as part of its Enterprise Asset Management system). This plan has not been made public, and Reinvent Albany FOIL requests for this information have been rejected or delayed. For more information about the MTA’s asset management process and the TAM requirements, see Reinvent Albany’s Open MTA report.7

Past 20-Year Needs and Draft Capital Plan Public Release Schedules

Reinvent Albany reviewed public documents on the MTA and NYS Library websites, as well as archives from the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA (PCAC) and NYC Transit Museum to find release times for past needs assessments and draft capital plans. A summary and chart is provided below, followed by a summary of the process in prior cycles.

- 2015-2019: The 20-year needs assessment was provided publicly in October 2013, 11 months in advance of the MTA Board’s vote on the draft capital plan. The draft plan was released shortly before the Board’s vote in September 2014.

- 2010-2014: The 20-year needs assessment and draft plan were both released publicly in August 2009 before the MTA Board vote in September 2009, one month in advance.

- 2005-2009: The 20-year needs assessment was released in March 2004, and a draft capital plan was provided to the public in July 2004 prior to the September 2004 approval by the MTA Board.

- 2000-2004: The draft capital program was not released until September 1999, right before the MTA Board vote. The 20-year needs assessment was not released until May 2000, after the plan was approved by the CPRB. Advocates decried the lack of transparency. Ultimately, a Regional Plan Association analysis comparing the 20-year needs assessment with the final capital plan found significant underfunding of NYCT. They conjectured that the CPRB would not have approved the plan had this information come to light sooner.

- 1992-1999: a 20-year needs assessment was released in May of 1990, and a draft capital plan was released 10 months later in March of 1991. The MTA Board voted on the draft plan in September 1991. The needs assessment came out a full 16 months before the Board vote. Note that this plan spans eight years as it was extended in 1995, three years into the plan, for another five years.9

- 1987-1991: a needs assessment was released to stakeholders in March of 1986. Information regarding the release of a draft capital plan and MTA Board vote could not be obtained.

- 1982-1986: a 10-year needs assessment was conducted in 1981, which was used to develop the capital plan.10 Information regarding the release of a draft capital plan and MTA Board vote could not be obtained.

Following release of needs assessments and draft capital plans, the MTA Board must vote on the draft plan by October 1st in the year prior to the start of the capital plan. The CPRB must then consider the capital plan within 90 days. Under a new requirement from the state budget this year, members of the CPRB that reject the plan must issue a written disapproval.11Additionally, the CPRB must follow the Open Meetings Law by approving the plan in a public meeting, though it has not done so in past cycles.12

The CPRB has typically approved the final plan in the first year of the capital plan, though approvals have dragged on longer in some cycles. The 2015-2019 capital plan did not receive final approval until May of 2016. In a review of the MTA’s capital plan process, AlixPartners, a consultant hired by the MTA to review its 2015-2019 capital plan, found that delayed approval of the capital plan has resulted in at a minimum the need for cost increases due to inflation, if not more substantial cost increases.13 Increased transparency of draft plans prior to a vote of the MTA Board could help to shorten the time frame for CPRB review of the plan, as any issues could be surfaced earlier in the process rather than later.

2019: A Year Unlike Any Other

Beyond having no public 20-year needs assessment or draft capital plan, the current lack of transparency and level of uncertainty regarding regarding the MTA’s 2020-2024 capital process is exceptional. Several reviews and audits are taking place simultaneously, an unusual development, and approval of the capital plan now requires more steps than in previous years. Together, these requirements have created a layer of chaos which opens up the ability of those who control the flow of information to limit public input.

- Traffic Mobility Review Board - This board, which has not yet been appointed, is charged with coming up with a recommendation for the central business tolling program, including any credits or discounts. It is also charged with reviewing the MTA capital plan, yet no details are provided in the law as to when this will occur, or whether this review could take the form of a veto.14

- Independent Forensic Audit - Due by January 1, 2020, this audit is mandated by law and will review the MTA capital program for a “detailed accounting of the authority’s capital elements.” While this review appears to be for past capital programs, Governor Andrew Cuomo stated in a letter to the MTA that their can be no new capital plan until this audit is completed.15

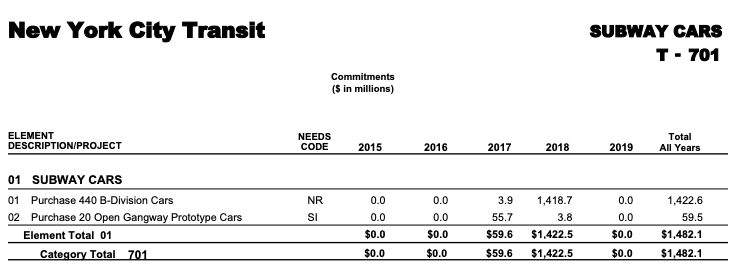

CEO/Chairman Pat Foye at an emergency meeting of the MTA Board on August 16th in response to public testimony asking for the draft plan to be released stated that the agencies strategic plans – New York City Transit’s Fast Forward, LIRR Forward, and Metro North’s Way Ahead Plan – are equivalent to capital plans. He noted that 200 community meetings were held on Fast Forward alone. This community outreach is commendable, but there should be no illusion that these documents are the legally mandated MTA capital program. These plans represent strategic plans that also include operating initiatives. They do not contain budgets, project schedules, funding sources, or other detailed information about whether itemized projects are for state of good repair or system expansion. Further, we do not know to what extent these plans are incorporated in the draft capital plan. What follows is a project listing from the 2015-2019 capital plan that shows the level of detail provided for individual projects, which is not included in the agency plans.

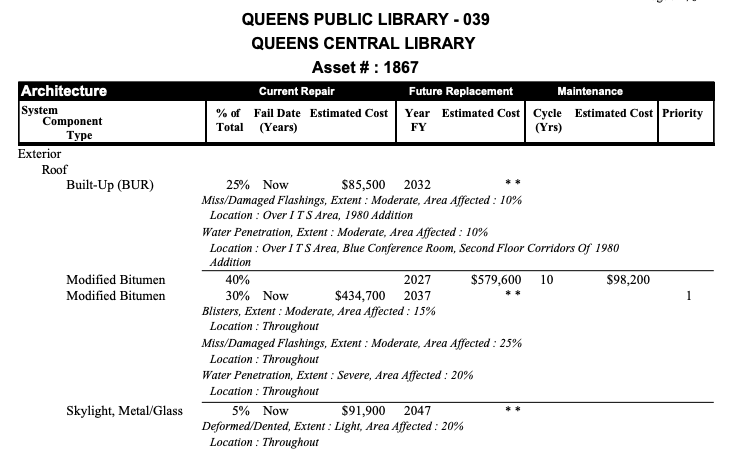

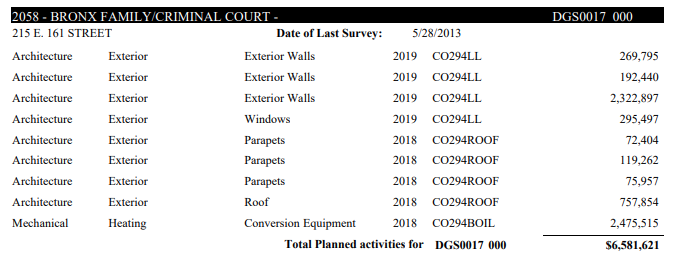

Appendix – Other Models for Asset Inventories

Other than through the 20-year needs assessment, the MTA has not publicly released a detailed listing of its assets. Section 1110-a of the New York City Charter creates an annual Asset Information Management System Report, also known as AIMS, which is released to the public and could serve as a model for public release of asset information by the MTA. AIMS includes a full inventory of NYC agencies’ capital assets, detailing for each component the date of construction or reconstruction, original cost, and a professional assessment of its remaining useful life and replacement cost. Below are examples of how this information is provided.