Watchdog Report: MTA Needs Congestion Pricing Money Now, Not in 2023

2020-2024 MTA Capital Plan Funding Coming in at Slowest Pace of Last 3 Plans:

MTA Has Just $2B of the $55B Budgeted

A new report from watchdog group Reinvent Albany finds that the MTA has on hand only $2 billion of the $55 billion it needs to complete the 2020-2024 capital plan.

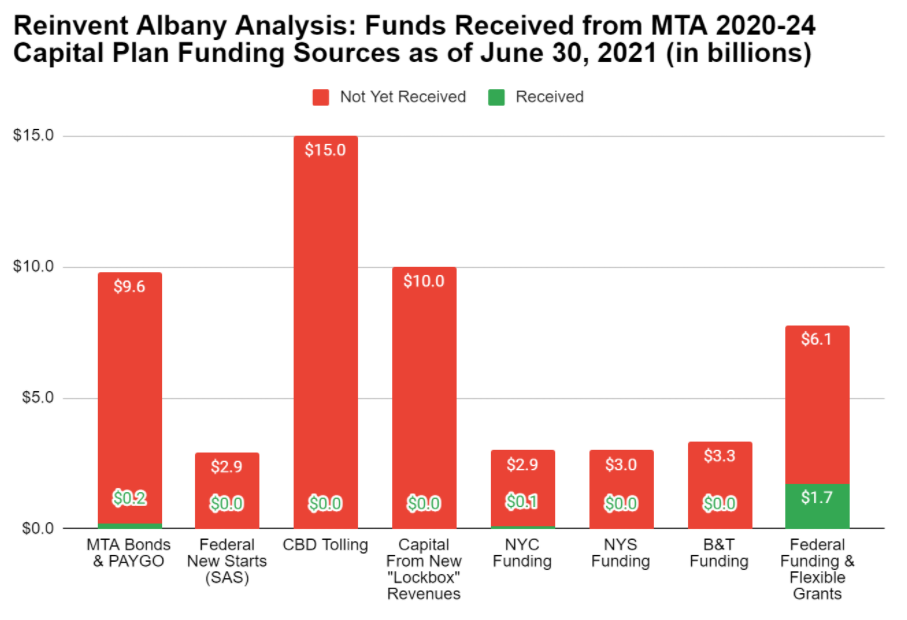

The single biggest piece of capital plan funding ‒ $15 billion ‒ is supposed to come from congestion pricing. But the pricing program, which was slated to launch in January 2021, won’t bring in revenue until 2023 at the earliest, according to the MTA’s latest financial plan.

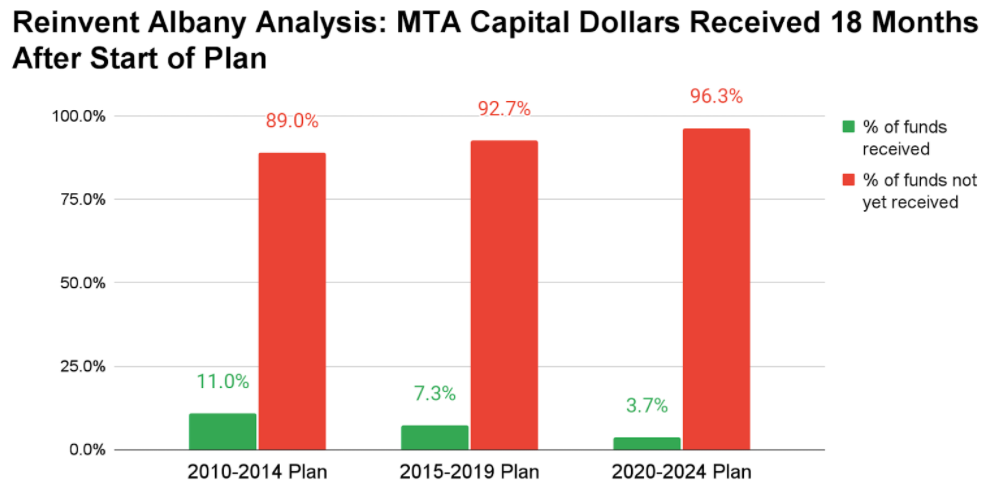

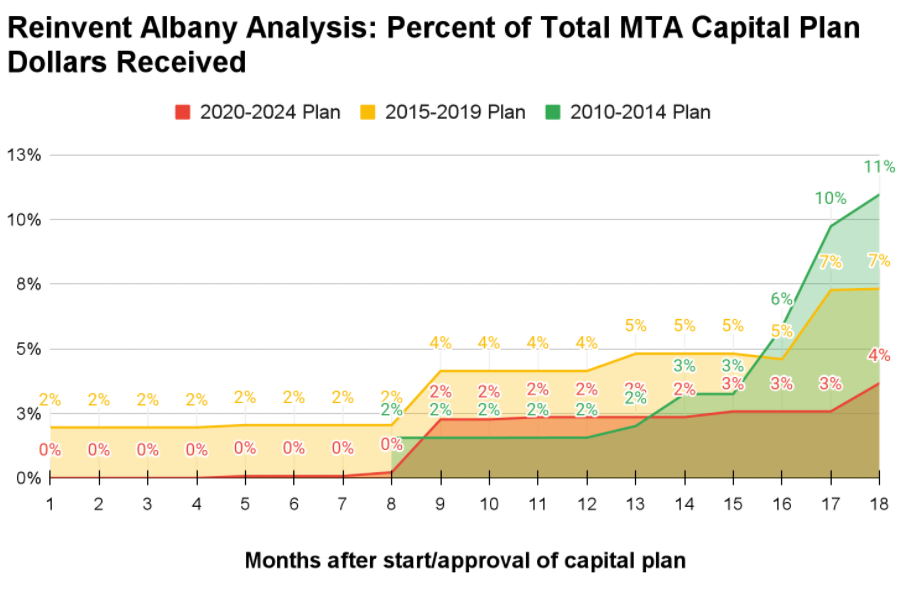

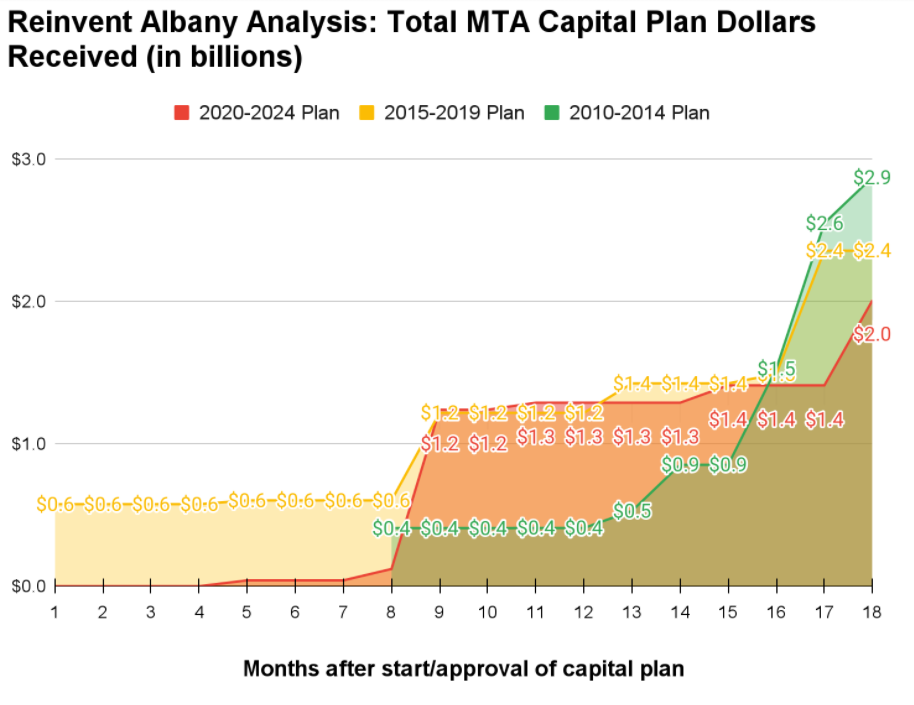

This is a historically slow pace compared to the last two capital plans, which were also slow starters. Eighteen months in, the 2020 plan is only 4% funded versus 7% and 11% for the previous plans. From an absolute dollars perspective, the plan lags behind the last two plans, with only $2 billion available compared to the high of $2.9 billion for the 2010-2014 plan (not adjusted for inflation).

Given the sluggish pace of capital dollars coming in, the report identifies a number of risks if congestion pricing revenues are delayed further, including:

- Decreasing the MTA’s financial stability. The MTA’s other sources of funding for the capital plan have either not yet been delivered at sufficient levels to meaningfully start the plan, or are at risk.

- Delays to the capital plan, including critical maintenance work conducted by MTA workers (i.e., TWU Local 100 members) that is reimbursed from the capital plan. Given the massive size of the 2020-2024 plan at nearly $55 billion dollars (almost double the size of previous plans), there is a real risk that this plan will not be able to be completed in a reasonable timeframe.

- Increased congestion on the roads, with fewer reasons to get people out of their cars and back onto mass transit—bringing in needed fare revenues. Congestion pricing is exactly what New York needs to recover from COVID to boost transit ridership and revenue and reduce the costs of traffic congestion.

The report also makes the case that time is money, and every day the MTA fails to get congestion pricing revenue, the MTA loses funds that could go to modern subway signals, new train cars, new buses and station accessibility.

COVID-19 put immense pressure on the MTA’s operating budget, which has led to gaps in its 2020-2024 capital plan due to the MTA’s use of deficit financing from the federal Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) program to stay afloat during COVID. The MLF borrowing has left a $2.9 billion hole in the capital program, according to the State Comptroller. The MTA also used nearly $500 million in lockbox funding from the internet sales tax and mansion tax in 2020 to fund its operating budget, which the MTA does not intend to replenish any time soon. Further, anticipated federal infrastructure funding will not replace lost congestion pricing revenue, because the MTA already budgeted for the federal funds.

“The MTA literally cannot afford to lose congestion pricing revenues,” said Rachael Fauss, Senior Research Analyst at Reinvent Albany, the lead author and researcher of the report. “The MTA, led by Governor Hochul, needs to quickly secure its crucial capital funding sources, including congestion pricing, as the agency recovers financially from the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“New Yorkers are sick and tired of the expense, anxiety and frustration that come from unreliable and inaccessible subway service,” said Betsy Plum, Executive Director of Riders Alliance. “We’re looking to incoming Governor Hochul to implement congestion pricing and finally fix the trains and buses we depend on. As our communities continue to recover, rebuild, and persevere, congestion pricing is the keystone policy that will at once tame New York’s costly gridlock and deliver the modern public transit system we need and deserve.”

The report is available below and in PDF here.

MTA Needs Congestion Pricing Money Now, Not in 2023

2020-2024 MTA Capital Plan Funding Coming in at Slowest Pace of Last 3 Plans:

MTA Has Just $2B of the $55B Budgeted

August 2021

The MTA has on hand only $2 billion of the $55 billion it needs to complete the 2020-2024 capital plan, according to an analysis of MTA finances by Reinvent Albany.

The single biggest piece of capital plan funding ‒ $15 billion ‒ is supposed to come from congestion pricing. But the pricing program, which was slated to launch in January 2021, won’t bring in revenue until 2023 at the earliest, according to the MTA.

Having only $2 billion at this stage is a historically slow pace compared to the last two capital plans, which were also slow starters. Eighteen months in, the 2020 plan is only 4% funded versus 7% and 11% for the previous plans.

Time is money, and every day the MTA fails to get congestion pricing revenue, the MTA loses funds that could go to modern subway signals, new train cars, new buses and station accessibility. Additionally, delayed money that eventually comes in will have less value due to its having to cover inflated costs for labor, materials and equipment. (Inflation on MTA mega-projects is typically much higher than the rate of inflation.)

Nevertheless, MTA officials have said, inexplicably, that there is no immediate need for congestion pricing funds to start its 2020-2024 capital plan. The MTA’s Chief Financial Officer Bob Foran said to the MTA Board in June 2021 that:

“Right now, we’re fronting the capital program with the sales tax monies and the mansion tax monies that we have…So we’re not in a position now to really be needing absolutely at this point in time, the congestion pricing proceeds for the capital program.”

What Foran did not say is that the MTA’s lockbox for the internet sales and mansion tax funds was busted open in 2020, diverting nearly $500 million from the capital program to the operating budget as fare revenue plummeted. Importantly, the MTA does not intend to replenish the capital funds from the lockbox funds anytime soon given financial troubles from COVID-19.

Timely implementation of congestion pricing is increasingly urgent for the MTA and the New York City metropolitan region. The MTA, led by Governor Kathy Hochul, who will control the authority upon taking office, needs to secure its crucial capital funding sources, including congestion pricing, as the agency recovers financially from the COVID-19 pandemic. More than just a funding source for the MTA, congestion pricing is an essential policy tool to reduce vehicle emissions that fuel global warming and traffic congestion that is like a tax on the cost of goods and services for everyone in New York.

While the Trump administration was initially responsible for delaying the pricing plan, the implementation calendar was placed squarely in the MTA’s hands in March 2021. At that time, the federal government formally notified the authority that a relatively modest Environmental Assessment (EA) would suffice for the agency’s review process.

New York State passed a law more than two years ago authorizing the MTA to create a congestion pricing zone in central Manhattan sufficient to net at least $1 billion annually. Everyday the MTA delays congestion pricing, it increases the risk of the following:

-

- Decreasing the MTA’s financial stability. The MTA’s other sources of funding for the capital plan have either not yet been delivered at sufficient levels to meaningfully start the plan, or are at risk.

- The MTA’s use of deficit financing from the federal Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) program to stay afloat during COVID has left a $2.9 billion hole in the capital program, according to the State Comptroller. This is why dedicated, lockboxed revenue streams like congestion pricing for bonding or PAYGO remain critical. Otherwise, the MTA issues bonds backed by fares that effectively lock in fare hikes.

- Federal infrastructure funding will not replace lost congestion pricing revenue, because the MTA already budgeted for the federal funds. The MTA’s approved 2020-2024 capital plan assumes $7.5 billion in federal formula dollars (typically from reauthorization bills), $2.9 billion for the Second Avenue Subway, and $275 million in flexible grants, for a total of $10.675 billion. Because of the MTA’s MLF borrowing, the authority has $3 billion less that it can finance from its own revenue sources. This means that some of the $10.5B it anticipates in federal funds may be used for projects that would have been self-financed by the MTA. At most, the MTA will have about $7.5B in federal funds left over for what it originally intended the federal government to fund in the 2020-2024 capital plan.

- The MTA already has a very high debt load, and more borrowing to make up lost revenues would put pressure on the operating budget and could force deep service cuts just as the MTA is trying desperately to rebuild its ridership. Debt service is currently 21% of operating revenues. Congestion pricing is a boon for the capital plan and the operating budget because it lessens fare-backed debt loads.

- Delays to the capital plan, including critical maintenance work conducted by MTA workers (i.e., TWU Local 100 members) that is reimbursed from the capital plan. Repairs to bring the subway system to a state of good repair and modernize the system’s failing signals, some of which employ 1930s-era technology, are a crucial component of the capital plan. This work is essential to improve subway service reliability and reduce crowding just as an influx of commuters return to the office.

- Cash is flowing into the 2020-2024 Capital Plan at the slowest pace of the last three capital plans, both in terms of the percentage of the total plan funds received, and absolute dollars received 18 months in. Given the massive size of the 2020-2024 plan at nearly $55 billion dollars (almost double the size of previous plans), there is a real risk that this plan will not be able to be completed in a reasonable timeframe.

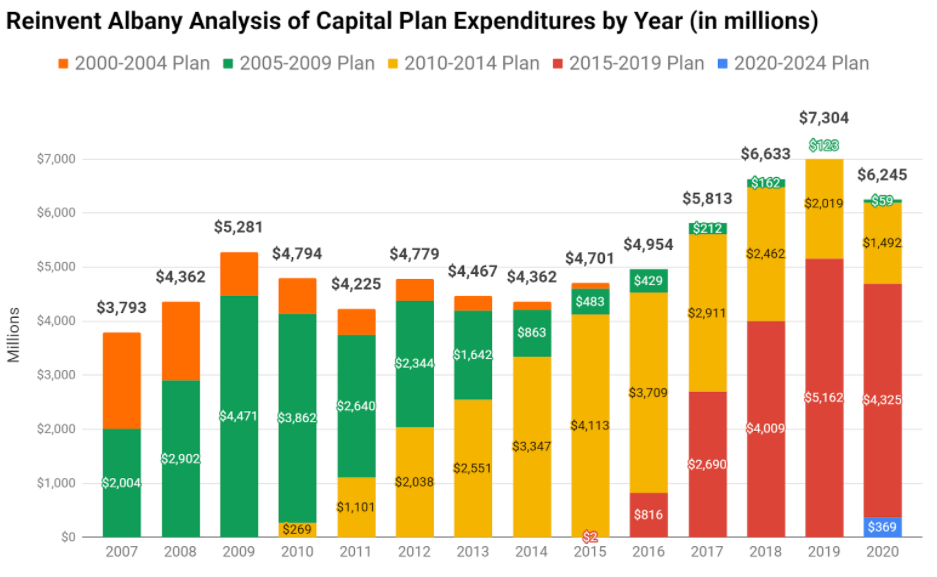

- Overall capital spending declined in 2020 due to COVID-19, slowing gains made in increasing MTA spending capacity in 2019. Given prior slow capital spending, this means that the MTA will have to accelerate its flow of money and spending in order to make meaningful progress on its capital programs.

- Increased congestion on the roads, with fewer reasons to get people out of their cars and back onto mass transit—bringing in needed fare revenues. Congestion pricing is an incentive program intended to encourage public transit and discourage peak hour driving. It is exactly what New York needs to recover from COVID to boost transit ridership and revenue and reduce the costs of traffic congestion.

Reinvent Albany’s analysis of revenues flowing into the 2020-2024 MTA capital plan is below.

Capital Dollars May Have Been Committed, But They Aren’t Flowing Yet

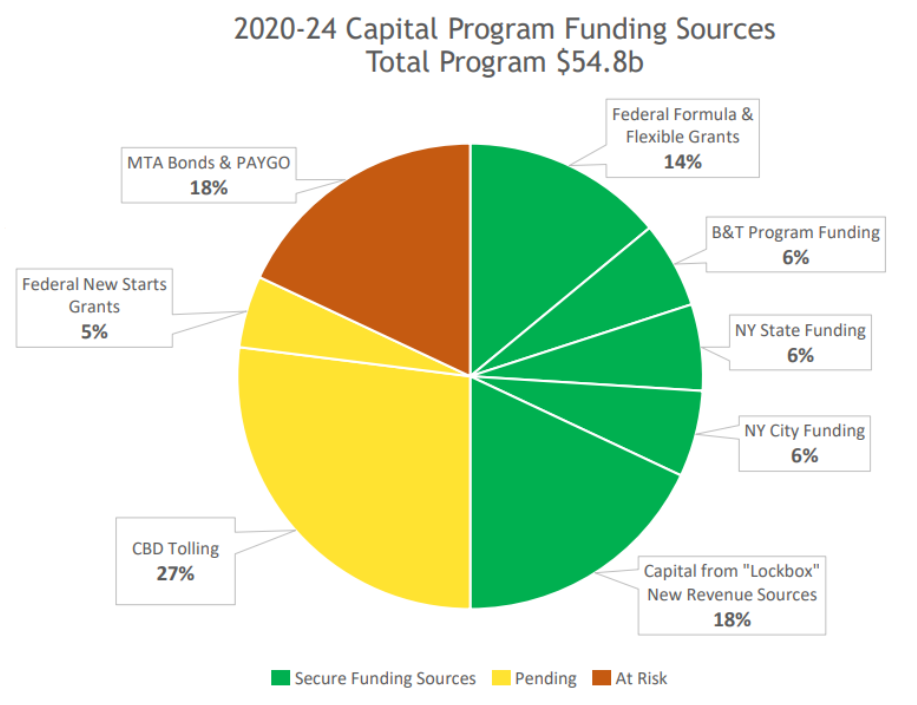

MTA Optimistically Says Half of Capital Plan is “Secure”

Although the MTA and Governor Cuomo announced in June 2020 that they “accelerated” capital work to take advantage of lower ridership during COVID-19, the pace of capital dollars coming in for the 2020-2024 capital plan has been sluggish. At the MTA’s July Board meeting, the authority released a chart classifying sources of the 2020-2024 capital plan as “secure,” “at risk” and “pending.” Only half of the plan was deemed “secure,” as shown in the green in the MTA’s chart below (from July 2021 MTA Board Capital Plan Update).

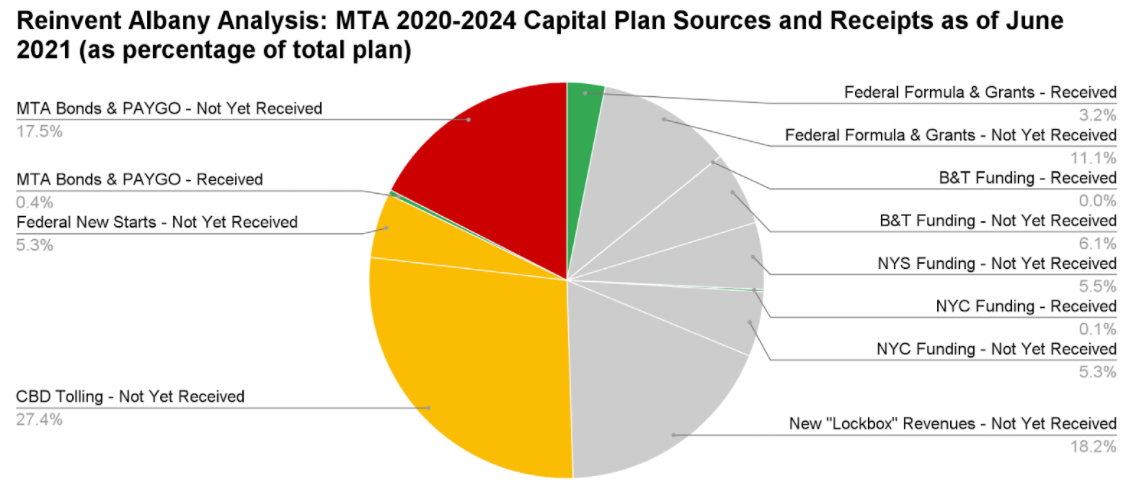

Less Than 4% of Capital Dollars Have Actually Come in, 18 Months into 2020-2024 PlanReinvent Albany’s charts, drawn from MTA Capital Program Oversight Committee materials from the July 2021 Board meeting, paint a grimmer picture. The MTA has not received 96% of budgeted capital funds as of the end of June 2021; only $2 billion had been received for the nearly $55 billion capital program, representing less than 4% of the plan.

If history is any indication, the state’s $3 billion capital contribution will come in late. Only half of the state’s $9 billion commitment to the 2015-2019 plan had been received as of June 2021 — eighteen months after the plan was supposed to be finished.While the MTA rightly has called its own borrowing capacity for the 2020-2024 plan “at risk,” this characterization does not tell the whole story. There is now a $2.9 billion hole in the MTA’s capital program, according to the State Comptroller. Because the MTA borrowed more than $2.9 billion from the federal Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) to cover its operating expenses in 2020, the MTA now will have to cut the program by the same amount, use federal infrastructure dollars, or further delay projects to preserve its original 2020-2024 plan projects. The MTA is still counting on the MLF funds to plug future operating deficits, according to its July 2021 financial plan presentation, particularly if it is to avoid future fare increases or service cuts.

Given the risks of delays to receipt of state funds, use of nearly $500 million in lockbox revenues in 2020 that is not likely to be paid back, and the inability for the MTA to borrow more money to fund its own contributions for the program, congestion pricing revenues are critical to stabilize the 2020-2024 plan’s state and city revenue streams.

MTA’s 2020-2024 Capital Plan Funding Coming in at Slowest Pace of Last 3 Plans

The rate of cash flow into the 2020-2024 Capital Plan is the slowest of the last three capital plans 18 months after their approval. This sluggish pace holds true both for the percentage of the total plan funds received, and absolute dollars received. Given the historic and massive size of the 2020-2024 plan at nearly $55 billion dollars, there is a real risk that this plan will not be able to be completed in a reasonable timeframe without revenues flowing in at a much faster rate.

As seen in the chart below, the MTA’s 2020-2024 capital plan has only received 3.7% of the funding needed to finance its projects 18 months into the plan. Compared to the last two plans, the 2020-2024 plan has the slowest pace: 7.3% of the 2015-2019 plan was received 18 months after approval of the plan, and 11% was received in the same time frame for the 2010-2014 plan.

The slow pace for the 2020-24 plan is also true in terms of absolute dollars received: only $2 billion has been received, compared to $2.4 billion for the 2015-2019 plan and $2.9 billion for the 2010-2014 plan 18 months in, as seen in the chart below.

Overall MTA Capital Spending Rate Declined in 2020 Due to COVID-19Given its ambitious 2020-2024 capital program and past slow performance at spending down its prior capital plans, the MTA can’t afford to have 2020-2024 capital dollars coming in at a sluggish rate. The MTA began to make gains in its capital spending capacity in 2019, breaking its prior records by spending a total of $7.3 billion on all of its capital plans. However, due to COVID-19 disruptions including a pause on new capital work and workforce impacts, the MTA spent only $6.2 billion in 2020, as seen below.

If the MTA is going to truly accelerate its capital program spending and meaningfully start its 2020-2024 capital program, it will need the funds to do so. This requires the MTA, led by Governor Kathy Hochul, to make the startup of congestion pricing an urgent priority.Acknowledgements:

Reinvent Albany staff produced this report, with research and writing by Rachael Fauss, Senior Research Analyst, and writing and editing assistance by John Kaehny, Executive Director and Tom Speaker, Policy Analyst. We thank Charlie Komanoff, Ben Fried of TransitCenter and Danny Pearlstein of Riders Alliance for their input and suggestions.

- Decreasing the MTA’s financial stability. The MTA’s other sources of funding for the capital plan have either not yet been delivered at sufficient levels to meaningfully start the plan, or are at risk.